T.E.M.P.S Question Design Standards

Published:

I’m often asked for specific guidance on designing sex, gender and sexuality survey questions. I’m in the process of producing a freely accessible online toolkit on this subject as well as an academic publication discussing trans data representation in more depth. However, this takes time and I know that there is a pressing gap in guidance. To help address this I am going to share the T.E.M.P.S question design standards. T.E.M.P.S represents five of the key recommendations based on my research with groups currently overlooked by UK population surveys(see information on my research design here).

These design standards were produced with population surveys in mind. The application of each standard will differ depending on the context. They may have some relevance to other data collection exercises on sex, gender and sexuality or other forms of demographic data but were not designed with these in mind.

Before using TEMPS you should first consider the following questions:

- Do you need this data?

- Do you understand how your target population discusses these characteristics?

- Can you communicate why you need the data, how you will use it and who can access it?

- Could giving you information benefit the most marginalised groups providing you with data?

If the answer to any of these is no then you should not be collecting this data. If you are wondering you probably don’t need data on sex assigned at birth so you shouldn’t be asking about it. If you are conducting medical research where sex characteristics may be significant consider asking directly about the relevant characteristics. This blog post focuses primarily on categorical gender and sexuality questions as well as trans status/gender modality questions.

There is a TLDR section at the end of this post that summaries the key points of the T.E.M.P.S question design standards without as much context or discussion. If you are questioning the assumptions behind your survey designs you’ve already taken the first step towards designing better surveys.

Text boxes for options not listed

Focus group and survey participants in my research emphasised the significance of including the ability to write in options not listed. Gender and sexuality questions without a text box limit the participants who can be represented to those recognised by survey designers who may or may not have a strong understanding of gender or sexuality.

Some survey designers in an attempt to recognise that not everyone will fall within the listed categories will include an “other” option. Participants in my research saw this as literal othering as it showed a lack of care about anyone who did not fall within the listed categories. Other options also tend to lump together what could be radically different populations. Until the data from the latest round of censuses is released the Annual Population Survey(APS) represents the Office of National Statistics’s (ONS) main tool for creating sexuality estimates for the UK. In 2020 0.7% of respondents to the Annual Population Survey(APS) sexual orientation question selected other (ONS, 2020). There was no text option for these respondents so there is no way to tell who if part of that 0.7%. Within my research some identifies expressed by my respondents that fell outside of the categories of lesbian, gay , bisexual and heterosexual were: asexual, demisexual, pansexual, aromantic, queer and polyamorous. These categories can vary significantly from each other so lumping them all together based on what they are not makes little sense. Yes, they may represent small groups and some grouping of observations may be required during analysis but hardcoding this into the design of the question limits the depth of analysis and can be seen as making a value judgment on who matters.

During the design process of the 2022 Scottish census, NRS with backing from LGBTI+ groups such as the Equality Network proposed the use of predictive text to help ensure text box responses were recorded the same way, making cleaning and analysing the data easier and saving some time for the participants. Despite the functional benefits of this, it was dropped due to the attitudes of the committee responsible for the census (Guyan, 2020). Adopting predictive text in online surveys could help maximise their functionality.

Expansive options informed by common text responses

Text box responses are harder to analyse (not impossible, so suck it up) and respondents in my research did note not being the main options listed could be seen as a judgment on their value and legitimacy. Yes, no survey question on gender or sexuality will ever be able to list all the ways that people identify but having as expansive a list as possible, informed by common responses to previous surveys can help create more inclusive surveys which are easier to analyse with fewer text responses.

Having a more expansive list of options can help address hetero/cis normative assumptions about the nature of gender and sexuality. If all gender questions include 2 options and all sexual orientation questions only record based on identifies associated with being attracted to one or both of those two options then claims about the nature of gender and sexuality are being made. This isn’t to say that the categories of lesbian, gay , bisexual or heterosexual assume a gender binary or that people who fall into these categories have sexualities defined in terms of gender but rather some people claim that is what sexual orientations questions are about. Surveys that include options like non-binary, gender fluid, queer, asexual and demisexual can help reinforce that gender is not a binary and our sexuality is not only tied to gender.

Assuming consistency of responses (which can’t be taken for granted) if the 374 respondents to the online survey I conducted were asked to answer a binary gender question then 131 would be unable to answer. If these same respondents were asked to answer sexuality questions with only the options, lesbian, gay, bisexual and heterosexual then 101 of them would be overlooked as they did not describe themselves using such terms.

Multiple options can be selected

Currently, survey questions on gender and sexuality ask you to select one option despite said options not being mutually exclusive. In my research, I provided survey respondents with the opportunity to select more than one gender and sexuality option and this is the data I collected.

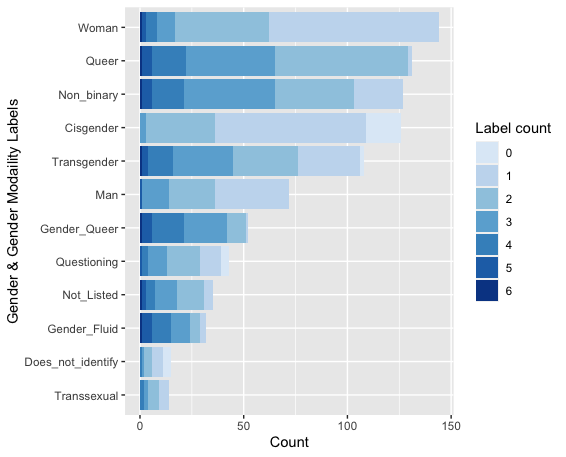

Figure 1: Survey responses to gender & gender modality questions + count of labels selected

Figure 1 shows how the 347 LGBTI+ people ages 16+ that I surveyed in the UK described their gender and gender modality and the number of different gender options they selected. I did not include the gender modality terms like transgender, transexual and cisgender in the count of gender terms as gender modality is a separate characteristic from gender. 170 respondents selected 2 or more gender options meaning that in a normal survey, even one with an expansive list of options at least 170 of these respondents would have an element of their gender overlooked.Assuming that when provided with a binary question respondents who stated they were men or women would still do so, then a binary sex/gender question would overlook 131 of the respondents to this survey completely and the intricacies of identities for 72 men and 144 women.

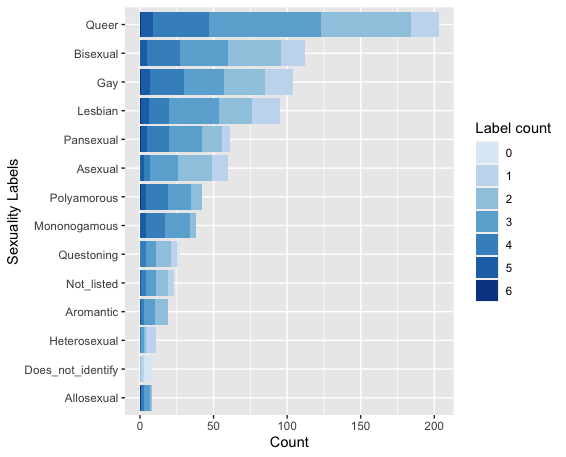

Figure 2: Survey responses to sexuality question + count of labels selected

Figure 2 indicates the same as Figure 1 but for the sexuality question. 202 respondents selected 2 or more options to this question (excluding the lesbians who also indicated they were gay (40)).

Respondents not fitting neatly within one box may be inconvenient in terms of analysis but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try to represent them accurately. We don’t know what analysis reflecting the complexity of gender and sexuality may uncover.

Prefer not to say options included

“I think when you say being visible, it’s like, being visible to whom, I would want to be told who I’m visible to. Whether this is on a database somewhere in the government, then people could pay to get access to it and who knows about me, we don’t know what they know about me, and that just freaks me out a bit.” (Jess a trans woman from the trans focus group who uses she/her)

As would be expected from reserach where respondents actively sought to participate most of the data collected was in favour of survey representation. However, there was still recognition of the risk of survey representation and some apprehension particularly surrounding who we could be becoming visible to.

Respondents emphasised knowing who was collecting the data, why and exactly how it would be used was important for them when deciding if to disclose information or not. Although my research focused on population surveys the respondents also discussed other situations where data is collected using survey questions. They noted that in many cases questions on matters such as gender were asked when they were not relevant, for example when logging onto public wifi or applying for a supermarket card. If respondents didn’t think the data was needed they didn’t want to answer a question.

In response to the online survey, one respondent noted that:

“These questions can help empower research and development and historical records, but if done incorrectly and without care, could also easily cause damage.” (A survey participant who drescibed themself as non-binary, gender queer,transgender, bisexual, pansexual, asexual, demisexual & queer)

This sums up the significance good question design can have and why allowing respondents not to answer is so important. Participants should be allowed to assess if disclosing information is in their best interest or not. Particularly given recent legitimisation of hostility towards LGBTI+ people.

Separate question each characteristic

Sometimes questions conflate characteristics asking about more than one at once. This can have three negative impacts:

- It can create confusion on what the question is asking about

- If it is clear what the question is asking it may take away some of the participants’ ability to choose what information they share

- It makes intersectional analysis where you look at issues on the basis of multiple characteristics more difficult

- It can send inaccurate messages about the nature of sex, gender and sexuality

The latest Australian census provides a clear example of issue one as its use of the term “non-binary sex” created confusion due to its conflation of non-binary genders and variations of sex characteristics(VSC). This issue has severely impacted the quality of the data making it useless for both non-binary people and people with VSC (Knott,2022).

Some question designs pair gender and gender modality together. Gender who someone is, gender modality is how that relates to their sex assigned at birth. Pairing these things together may make it so trans people can’t disclose one element of themselves without disclosing the other. It may also separate trans men and women from men and women generally, which is not only a harmful and inaccurate message but adds extra steps for researchers wishing to look at the experiences of all men and women trans and cis alike.

The trans status/gender modality question utilised in the latest censuses in England, Wales and Scotland has sometimes been referred to as a gender identity question. Although this question does feature a text box for trans people to specify their gender it is primarily about gender modality. My worry is that by calling this type of question a gender identity question it infers that gender is this less legitimate thing only trans people possess.

TLDR: T.E.M.P.S

When designing questions ask yourself:

Text boxes:

Does this question need a text box? If it is a categorical question asking respondents to select from a range of genders or sexualities then the answer is likely yes.

Expansive questons:

Does this question need more options? If it is a categorical question asking respondents to select from a range of genders or sexualities then the answer is likely yes. You could find other options by looking at common text box responses to questions like your own.

Multiple options:

Should your participants be able to select more than one option? If it is a categorical question asking respondents to select from a range of genders or sexualities then the answer is likely yes.

Prefer not to say option:

Should participants be able to tick a “prefer not to say” box if they do not want to answer a particular question but still participate in the rest of the survey? The answer is always yes.

Seperate questions for each charteristic:

Does your survey ask about more than one characteristic using one question? For example, do you use a trans status/gender modality question which also lets trans people write in their gender identity? It could be better to separate that out into two questions so it’s easier to analyse and participants can choose to disclose each bit of information separately.

Authors note on the use of T.E.M.P.S

If you find the T.E.M.P.S Question Design Standards helpful please incorporate them into your work. I would ask if you do so that you cite this blog post. These standards are based on an ethically approved PhD project funded by the University of Glasgow College of Social Sciences Scholarship. Keep an eye out for my future publications on survey design either here or on my Twitter. Citation in Harvard format:

English, K (2022) T.E.M.P.S. Question Design Standards, Available at: https://kenglish95.github.io/posts/2022/06/TEMPS